How dogs learn?

This page provides an overview of how modern balanced training methods have evolved. Balanced training is not the dogma of a single school of thought, but the logical continuation of insights from multiple behavioral sciences. Dogs do not learn through a single mechanism, and any approach that ignores parts of the learning process will inevitably remain incomplete. To understand this, it is necessary to look at how scientists have historically studied learning and what those findings actually mean in the context of dogs.

Ivan Pavlov and Classical Conditioning – How Learning Actually Begins

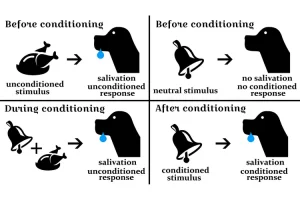

Ivan Pavlov was not a dog trainer or a behaviorist in the modern sense of the word. He was a physiologist whose research focused on digestion and the functioning of the nervous system. While studying dogs’ digestive responses, Pavlov observed that salivation did not occur only when food was placed directly in the mouth, but also began before feeding—triggered by signals such as the footsteps of a laboratory assistant, a specific sound, or other environmental cues that regularly preceded food delivery (Pavlov, 1927).

These observations led Pavlov to conduct systematic experiments in which he paired an initially neutral stimulus—such as the sound of a bell or a metronome—with the presentation of food. When this pairing was repeated often enough, the dog began to salivate in response to the sound alone, even in the absence of food. Pavlov termed this phenomenon a conditioned reflex and distinguished it from an unconditioned reflex, which is innate and does not require learning. His central conclusion was that organisms learn associations between events, and that these associations trigger automatic physiological and emotional responses (Pavlov, 1927; Domjan, 2018).

The significance of this discovery for dog training is fundamental. Pavlov demonstrated that learning always begins with meaning, not with conscious behavior. A dog does not decide whether to feel anxious, aroused, or calm—these states arise automatically when the environment resembles past experiences. Behavior is the visible outcome of this process, not its cause. Later researchers emphasized that classical conditioning is not merely the formation of a reflex, but learning about what predicts what (Rescorla, 1988).

In dog training, this means that many behavioral problems are not primarily issues of obedience, but emotional responses. A leash may be classically associated with tension, another dog may signal threat, and the sight of wildlife may trigger a strong predatory response. These reactions occur before the dog has any opportunity to “choose” a behavior. Pavlov’s work explains why such responses cannot be eliminated through obedience commands alone—they are not deliberate, but learned at the level of the nervous system (LeDoux, 1996). To develop impulse control in dogs, we must therefore understand how to access and influence behavior patterns learned at the neural level.

From the perspective of balanced dog training, Pavlov’s framework sets clear limits on what operant training alone can achieve. When a dog is in a state of intense fear, stress, or arousal, its capacity for learning is significantly reduced. Before shaping behavior, the meaning the dog assigns to the situation must be changed. This may involve creating new associations, weakening existing ones, or restructuring the environment (Bouton, 2007).

It is important to emphasize that classical conditioning is a value-neutral mechanism. The same process that allows for the creation of calm and secure associations can also produce strong fear or avoidance. For this reason, science-based training emphasizes precision and timing. The critical question is not whether a stimulus is pleasant or unpleasant, but what it becomes associated with and how broadly that association generalizes. Uncontrolled or imprecise pairing can lead to emotional generalization, which in turn negatively affects behavior (Domjan, 2018).

Pavlov’s work also helps explain why dogs often react before a human does anything overt. Body posture, breathing patterns, movement, or subtle environmental changes can all function as classically conditioned signals that have acquired meaning over time. A trainer who fails to recognize these cues may inadvertently reinforce a problem, even while applying technically correct techniques.

For this reason, Pavlov’s framework teaches that dog training does not begin with commands or tools, but with the nervous system. Learning is first a biological and emotional process, and only afterward a behavioral one. Balanced dog training takes this as its starting point and always asks, before intervening: what state is the dog in, and what associations is it currently carrying?

B. F. Skinner and Operant Conditioning – Why Behavior Persists or Disappears

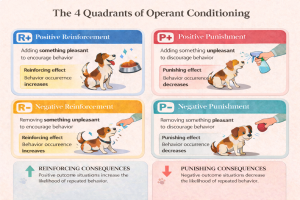

B. F. Skinner approached learning from a perspective somewhat different from Pavlov’s. He was less concerned with the emotional state of the animal and more interested in why one behavior repeats while another does not. Through his experiments, later conducted using what became known as the operant conditioning chamber, Skinner demonstrated that the frequency of behavior is determined by its consequences. Behavior that leads to a desired outcome or removes an unpleasant situation tends to increase, while behavior that becomes costly or no longer “works” gradually decreases (Skinner, 1938; 1953).

Skinner’s key contribution was the insight that behavior can persist even when it is harmful to the organism or socially unacceptable, provided that the structure of consequences continues to support it. This explains why problem behaviors—such as aggression, pulling on the leash, or reactivity—may persist despite good intentions and generous use of rewards. In dog training, this means that before introducing new techniques, it is essential to ask which consequences are currently maintaining the existing behavior.

Skinner’s key contribution was the insight that behavior can persist even when it is harmful to the organism or socially unacceptable, provided that the structure of consequences continues to support it. This explains why problem behaviors—such as aggression, pulling on the leash, or reactivity—may persist despite good intentions and generous use of rewards. In dog training, this means that before introducing new techniques, it is essential to ask which consequences are currently maintaining the existing behavior.

Operant conditioning does not automatically imply punishment. Skinner described four primary mechanisms through which consequences shape behavior. Positive and negative reinforcement increase the likelihood of a behavior, while positive and negative punishment decrease it. Balanced dog training uses these mechanisms not ideologically, but functionally. Positive reinforcement builds skills and motivation; negative reinforcement teaches the dog how to control or terminate discomfort; negative punishment clarifies that inappropriate behavior does not lead to the desired outcome; and positive punishment serves as a boundary-setting tool in situations where risk is high and alternatives are not feasible.

It is important to emphasize that Skinner’s framework does not address intention or “character.” Behavior is not good or bad—it either works or it does not. In dog training, this perspective removes moral judgment and shifts the focus toward modifying the environment and consequences so that the desired behavior becomes the most reasonable option for the dog. Later syntheses have shown that operant learning always occurs within a specific context and is strongly influenced by prior classical conditioning (Bouton, 2007).

Ethology – Why Dogs Behave the Way They Do

While Pavlov and Skinner focused on the mechanisms of learning, ethology seeks to answer a different question: why does this behavior exist at all? Ethology is the study of animals’ natural behavior within their biological and evolutionary context. Key figures in this field were Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen, who demonstrated that many behavioral patterns are species-specific and partially innate.

Tinbergen emphasized that behavior cannot be understood without addressing four questions: what mechanism triggers it, how it develops over the course of life, what function it serves, and how it evolved (Tinbergen, 1963). In dogs, this means that prey drive, territoriality, social distance, and body language are not “training mistakes,” but biological strategies that have been advantageous for the species.

From a dog-training perspective, ethology is critical because it sets limits on learning. Not everything can be freely shaped, and not all behavior is purely learned. Balanced training does not attempt to eliminate instincts, but to guide and constrain how they are expressed. When an instinct leads to dangerous or socially unacceptable behavior, it does not mean the dog is “broken,” but that training must take biological context into account.

The ethological perspective also explains why, in certain situations, reward-based approaches alone may be insufficient. When behavior is strongly motivated and functionally successful, it may be necessary to increase the cost of that behavior. This is where ethology and operant conditioning intersect: instinct provides direction, while operant learning determines whether and how that direction is realized in real life (Alcock, 2013).

Evolutionary Psychology – Why Avoidance Is a Natural Learning Strategy

Evolutionary psychology extends ethology by focusing on the mental and learning mechanisms shaped by natural selection. From this perspective, learning is not a neutral process, but one adapted for survival. Organisms that quickly learned to avoid danger and unpleasant consequences were more likely to survive and reproduce than those that did not (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992).

In dogs, this means that avoidance and learning from unpleasant experiences are not deviations, but part of their cognitive heritage. The nervous system has evolved so that signals predicting danger acquire meaning rapidly and exert a strong influence on behavior. This explains why aversive stimuli can be highly effective in learning, but also why their misuse can lead to generalized fear.

Balanced dog training applies insights from evolutionary psychology to ensure that interventions remain precise and proportional. The goal is not to induce fear, but to create clarity. When boundaries are consistent and logical, the need for intervention decreases, and the dog can operate within a predictable framework. An evolutionary perspective helps explain why dogs do not learn exclusively through positive experiences and why, in certain situations, avoidance can be more effective than competing with food rewards (Buss, 2019).

References

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Oxford University Press.

Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It’s not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151–160.

Domjan, M. (2018). The Principles of Learning and Behavior (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

LeDoux, J. (1996). The Emotional Brain. Simon & Schuster.

Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and Behavior: A Contemporary Synthesis. Sinauer.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. Macmillan.

Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and Behavior: A Contemporary Synthesis. Sinauer.

Tinbergen, N. (1963). On aims and methods of ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20, 410–433.

Lorenz, K. (1950). The comparative method in studying innate behavior patterns. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology, 4, 221–268.

Alcock, J. (2013). Animal Behavior: An Evolutionary Approach. Sinauer.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1992). The psychological foundations of culture. In The Adapted Mind. Oxford University Press.

Buss, D. M. (2019). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind (6th ed.). Routledge.